Construction of the Colorado River Aqueduct

Historical Background The Colorado River Aqueduct, constructed between 1933 - 1941, was at the time the largest water supply line in the United States. The aqueduct begins at the Parker Dam southeast of Lake Havasu City, Arizona, and terminates at Lake Mathews in western Riverside County, Calif. Conceived by William Mulholland and designed by Frank E. Weymouth, it was also the largest public works project in southern California during the Great Depression. The project employed 30,000 people over an eight-year period and as many as 10,000 at one time. |

|

|

| (1931) - Three leaders in community planning that brought Colorado River water to Southern California. On a desert survey trip at the start of the huge aqueduct project in 1931 were (left to right) F. E. Weymouth, who built the aqueduct; William Mulholland, who conceived it; and W. P. Whitsett, first chairman of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. |

The Colorado River: A Regional Solution**

William Mulholland turned east to the Colorado River as a new source of water. He began a four-year series of surveys in 1923 to find an alignment that would bring the water of the Colorado River to Los Angeles.

In 1925 the Department of Water and Power (DWP) was established and the voters of Los Angeles approved a $2 million bond issue to perform the engineering for the Colorado River Aqueduct. The DWP brought the cities of the region together with  Los Angeles in 1928 to form a state special district. An act of the State Legislature created the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California (MWD). Its original purpose was to construct the Colorado River Aqueduct to supply supplemental water to Southern California. In 1931, voters approved a $220 million bond issue for construction, and work began on the ten-year project that would bring the water 300 miles to the coast.

Los Angeles in 1928 to form a state special district. An act of the State Legislature created the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California (MWD). Its original purpose was to construct the Colorado River Aqueduct to supply supplemental water to Southern California. In 1931, voters approved a $220 million bond issue for construction, and work began on the ten-year project that would bring the water 300 miles to the coast.

Part of the success of the project was the spectacular Boulder Canyon project, now known as Hoover Dam. The DWP, manager of its own hydroelectric power facilities along the Los Angeles Aqueduct, was instrumental in the struggle to gain federal approval for the project which combined flood control, water supply, and energy production for the three states that form the lower Colorado River basin.

Los Angeles, as primary consumer of the power, guaranteed its power purchases against the federal government’s costs for the dam. Completed in 1935, the dam began furnishing power to the city the following year over a 226-mile transmission line built by the DWP.

Upon the completion of the Colorado River Aqueduct in 1941, MWD began to wholesale Colorado River water to its member agencies. Today those agencies include 14 cities, 12 municipal water districts, and a county water authority. More than 130 municipalities and many unincorporated areas are served by this project of the DWP’s and Mulholland’s vision.

Before his death on July 22, 1935, Mulholland lived to see the beginnings of the Colorado River Aqueduct and Hoover Dam, constructed in the spirit of greatness he had always envisioned for Los Angeles.

|

|

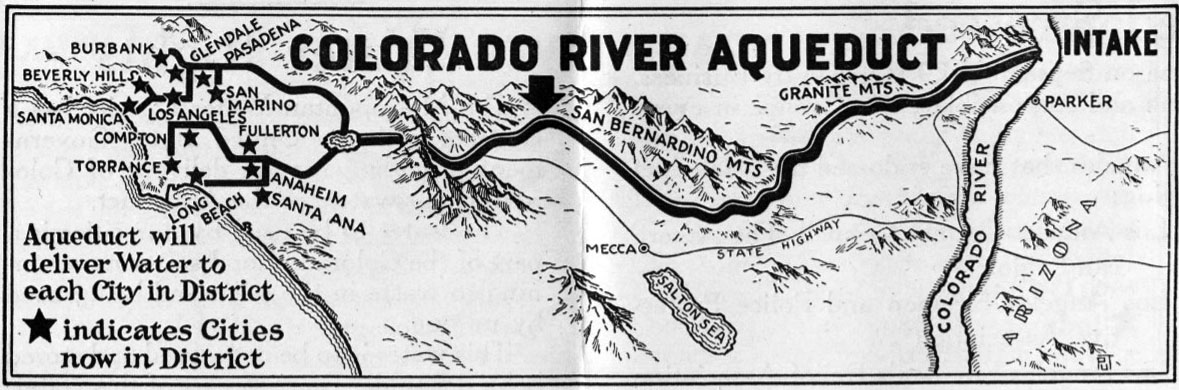

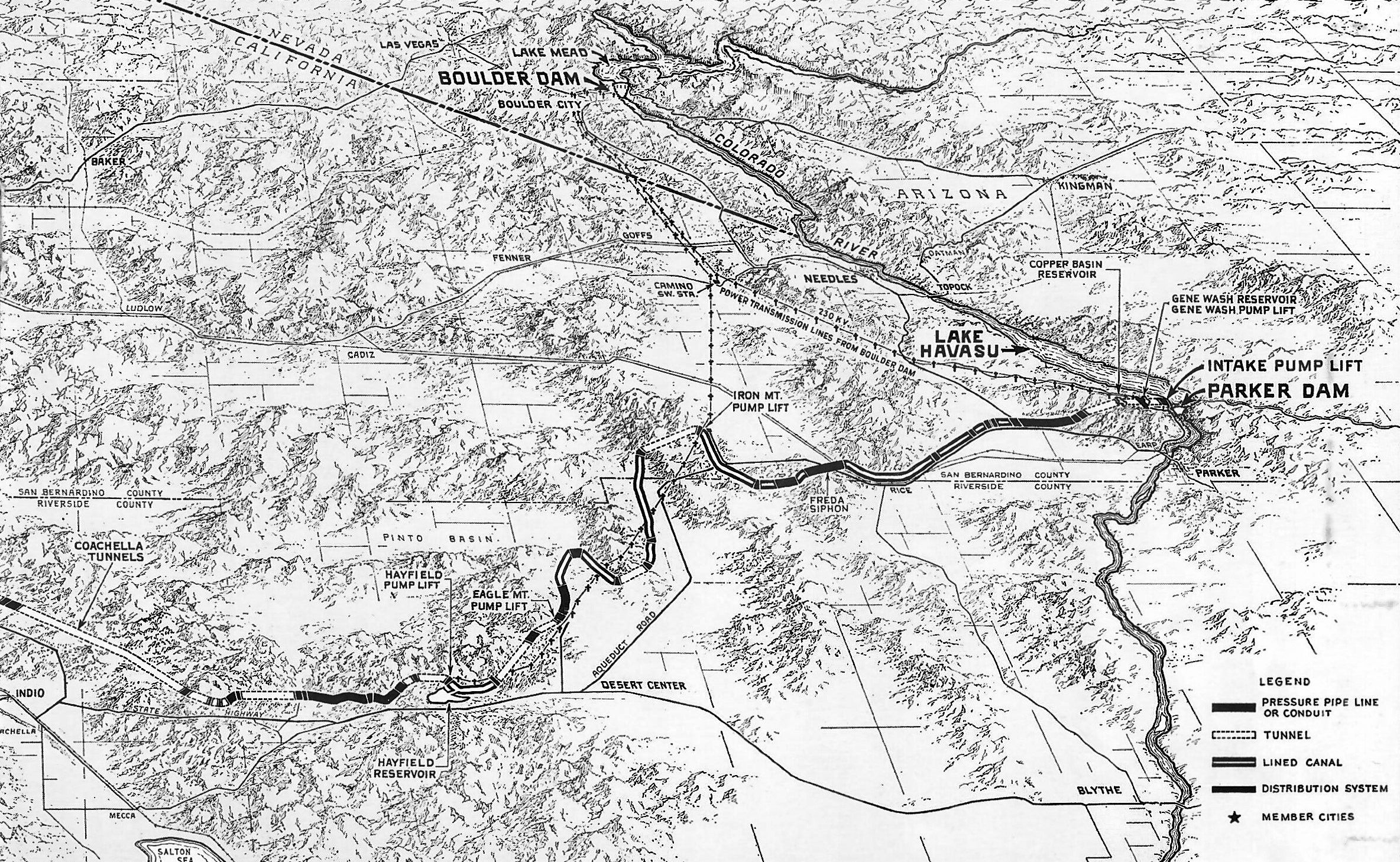

| (1931)*# – Map showing routing of the Colorado River Aqueduct. |

Historical Notes The MWD considered eight routes for the aqueduct. In 1931, the MWD board of directors chose the Parker route which would require the building of the Parker Dam. The Parker route was chosen because it was seen as the safest and most economical. A $220 million bond was approved on September 29, 1931. Work began in January 1933 near Thousand Palms, and in 1934 the United States Bureau of Reclamation began work on the Parker Dam. Construction of the aqueduct was finished in 1935. Water first flowed in the aqueduct on January 7, 1939. The Colorado River Aqueduct (CRA) begins near Parker Dam on the Colorado River. There, the water is pumped up the Whipple Mountains where the water emerges and begins flowing through 60 mi f siphons and open canals on the southern Mojave Desert. At Iron Mountain, the water is again lifted, 144 ft. The aqueduct then turns southwest towards the Eagle Mountains. There the water is lifted two more times, first by 438 ft to an elevation of more than 1,400 ft, then by 441 ft to an elevation of 1,800 ft above sea level. The CRA then runs through the deserts of the Coachella Valley and through the San Gorgonio Pass. Near Cabazon, the aqueduct begins to run underground until it enters the San Jacinto Tunnel at the base of the San Jacinto Mountains. On the other side of the mountains the aqueduct continues to run underground until it reaches the terminus at Lake Mathews. From there, 156 mi of distribution lines, along with eight more tunnels, delivers water to member cities. Some of the water is siphoned off in San Jacinto via the San Diego canal, part of the San Diego Aqueduct that delivers water to San Diego County.*^ |

|

|

| (1930s)^ - View showing the Colorado River from which water is diverted into the Colorado River Aqueduct and transported to the coastal plain of Southern California. |

Historical Notes Fed by melting snows from the western slopes of the Rocky Mountains, a water shed covering approximately 245,000 square miles, this is one of the great rivers of the North American continent. Its history in the development of the present civilization in America dates beyond that of the Pilgrims. The Colorado River was discovered in 1540 by the Spanish Conquistadores, Alarcon and Coronado. |

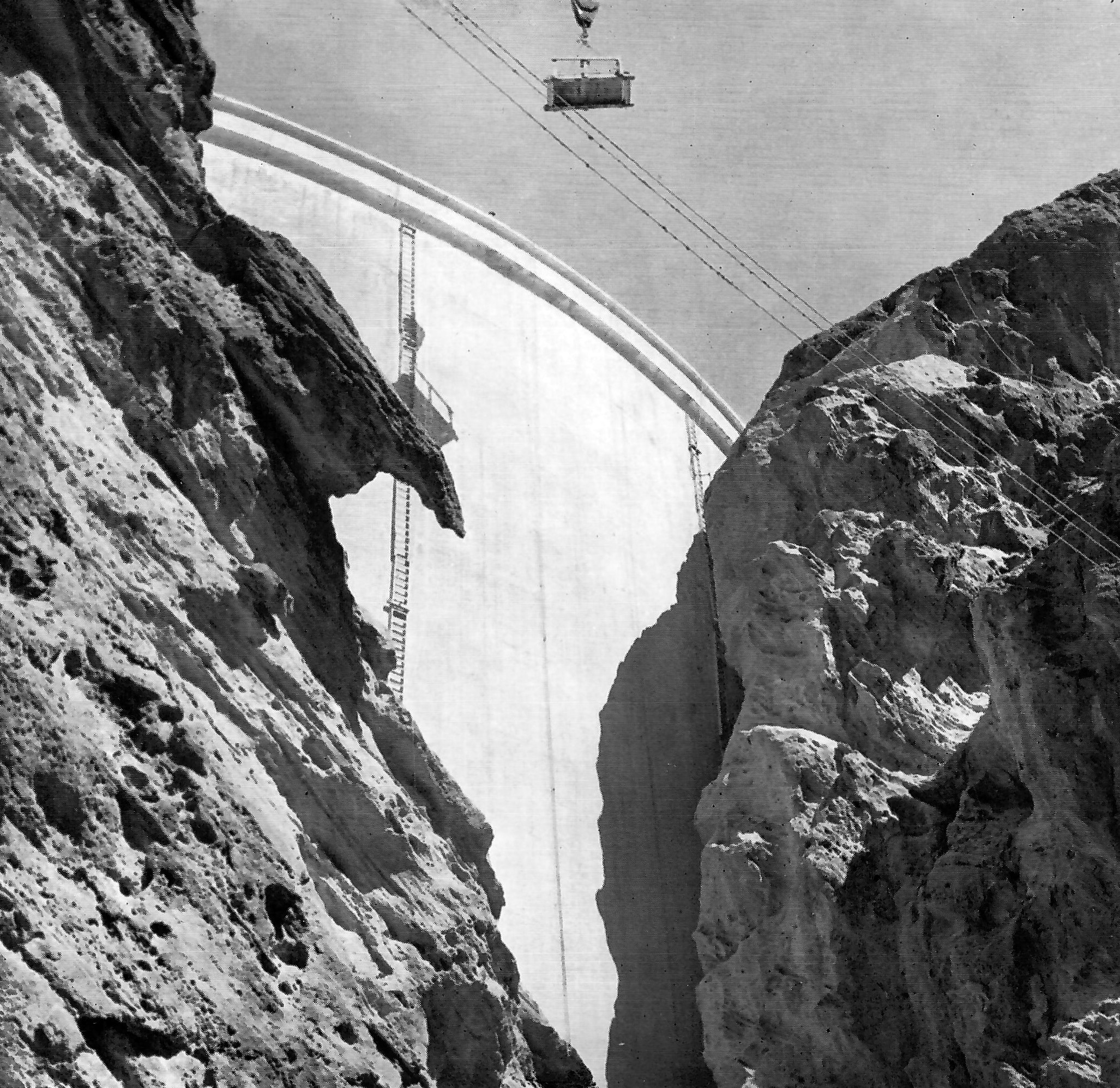

Parker Dam

|

|

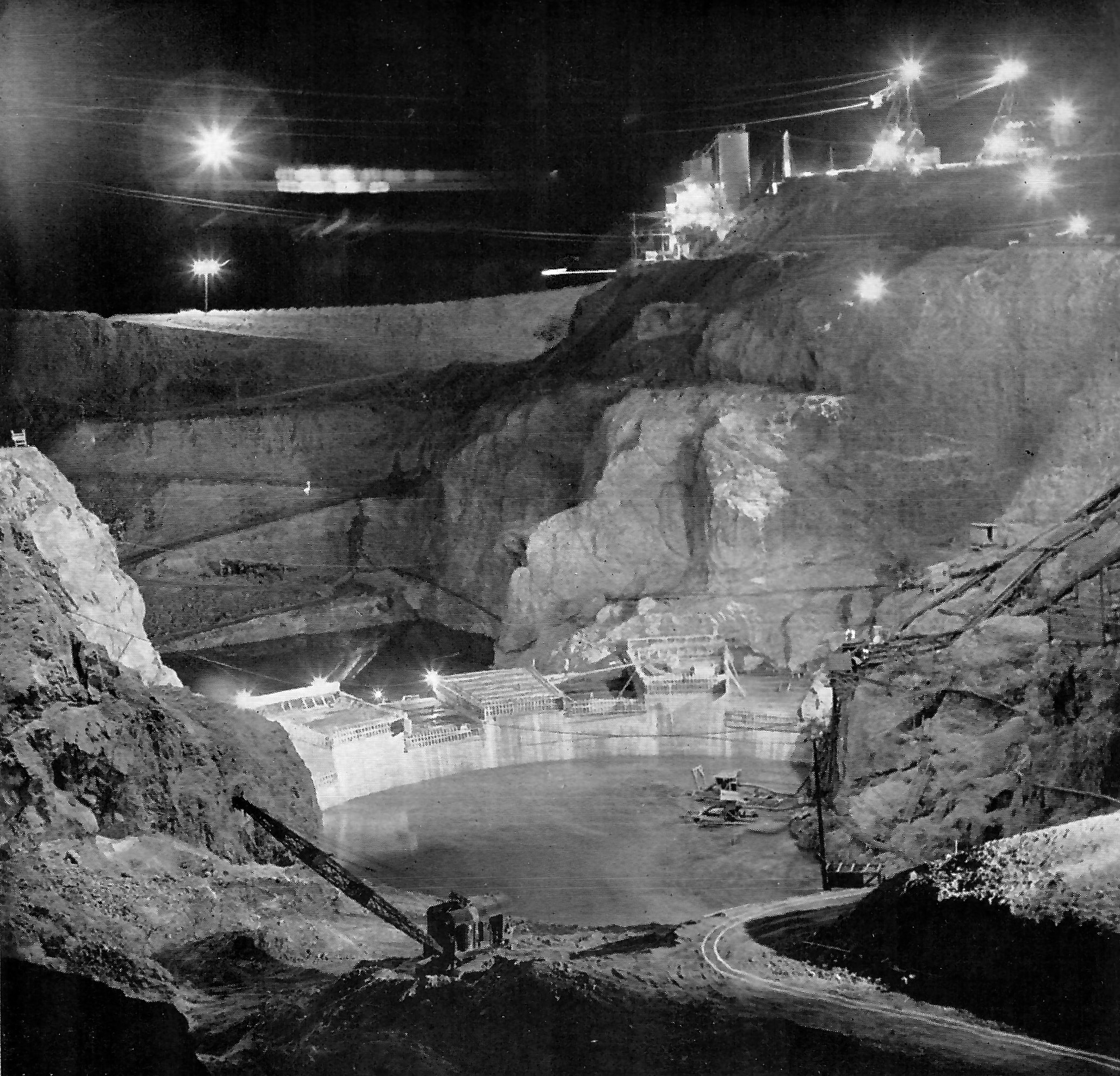

| (1937)^ - Excavation for Parker Dam. This picture vivdly illustrates the vast amount of excavation that was necessary in order to reach the bedrock on which the foundation of the dam was built. |

Historical Notes At the time the above picture was taken the bottom of the excavation was 204 feet below the original bed of the Colorado River. The foundation of the dam was actually placed on bedrock 233 feet below the original bed of the river, and for this reason Park Dam is known as the deepest dam in the world. |

|

|

| (1937)* - Night view of Parker Dam under construction. This midnight view of Parker Dam construction was taken in October, 1937, when the top of the rising dam was still more than a hundred feet below the surface of the Colorado River which was held in check by the high coffer dam seen in the left background. |

Historical Notes Construction work on Parker Dam and most of the other features of the Colorado River Aqueduct was carried on 24 hours a day. |

|

|

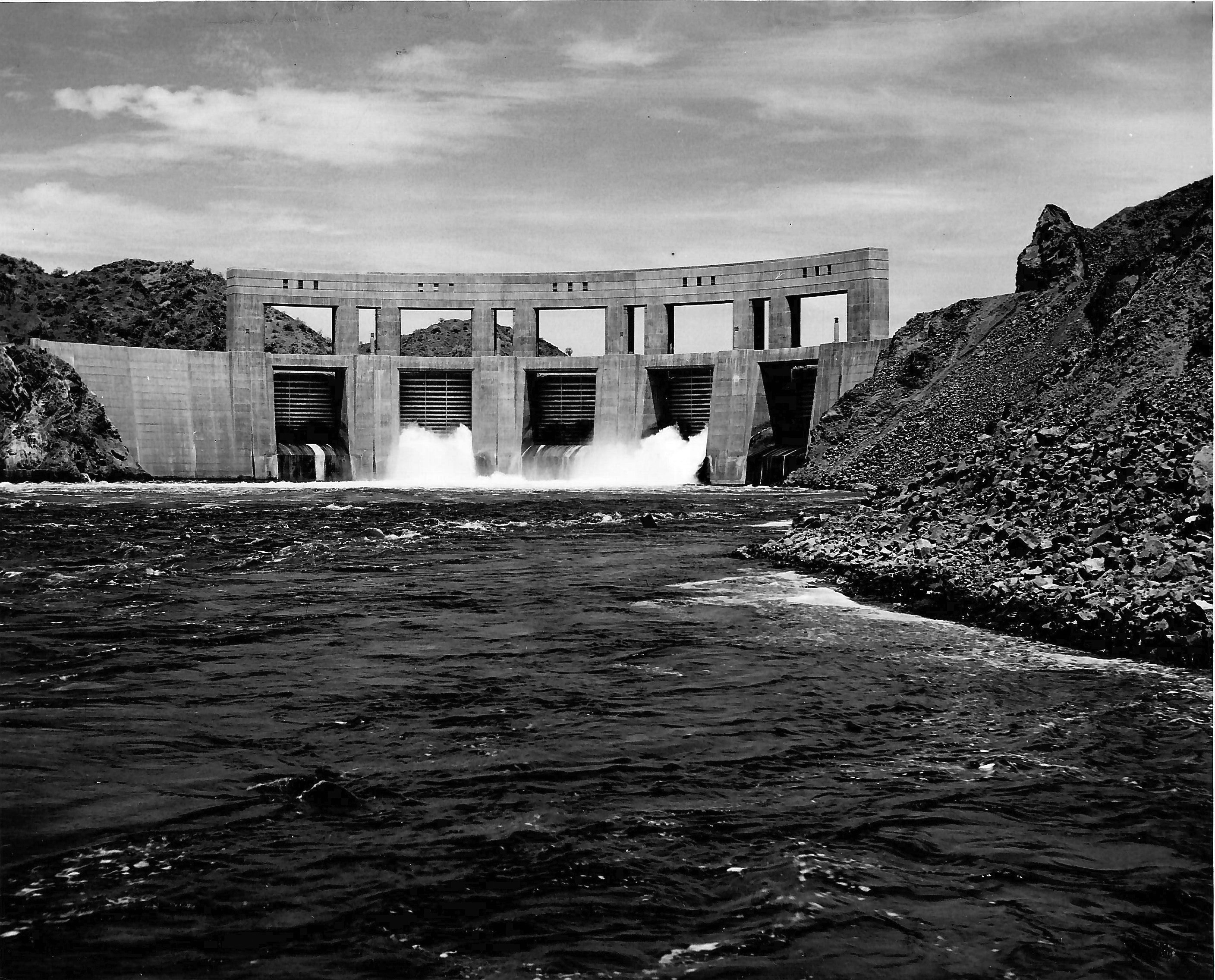

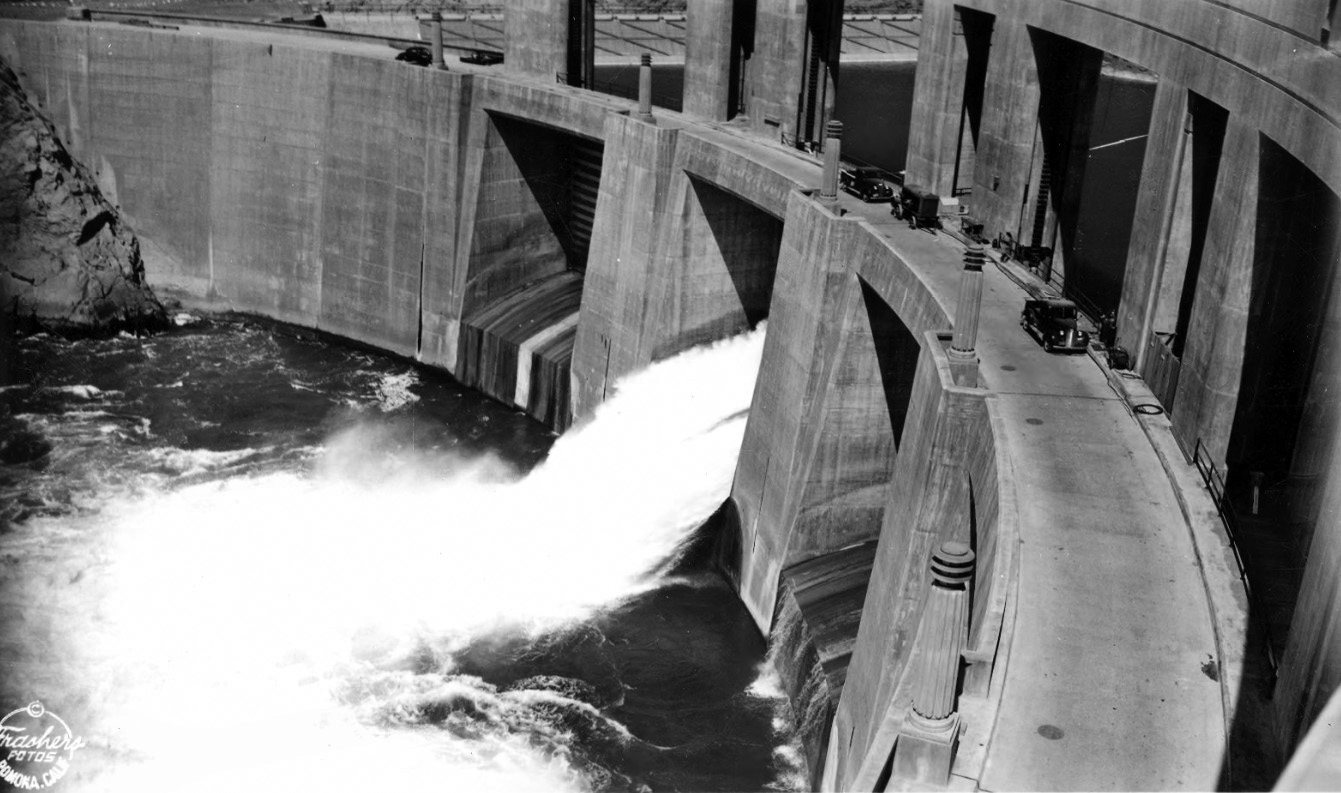

| (1938)^* - View showing Parker Dam on the Colorado River shortly after it was completed. This is where the Colorado Aqueduct begins. Photo courtesy of Mary Jo Holmes in Memory of her Father, Joseph Holmes, who worked on the construction of the aqueduct.^* |

Historical Notes At the time it was built, Parker Dam was known as "the deepest dam in the world" because it was necessary to excavate to a depth of 247 feet below the river bed to reach bedrock foundation. It was built primarily to re-regulate the Colorado River below Boulder Dam and create a reservoir, known as Lake Havasu, as a dependable water supply source for the giant Colorado River Aqueduct. Parker Dam was built by the US Government with funds supplied by the Medtropolitan Water District. |

|

|

| (1939)^.^ - Aerial view showing Parker Dam and Lake Havasu on the Colorado River. |

Historical Notes Construction of the dam was a contentious issue for Arizona. Built as part of the larger Colorado River Compact of 1922, several political groups, their members and privately owned utility companies in Arizona were not pleased with the plan in general and refused to sign it until 1944. Even then Arizona continued to dispute its water allotments until a 1963 Supreme Court decision settled the issue. The court has had to adjust the agreement several times since, most recently in 2000. As recently as 2008 Arizona Senator John McCain called for a renegotiation of the plan.^ |

|

|

| (1940)^^ - Postcard close-up view showing Parker Dam with several vehicles parked on the road that crosses the dam. |

Historical Notes In 1935, when Arizona Governor Benjamin Baker Moeur sent 6 members of the Arizona National Guard to observe the dam's construction, they reported back that there was construction activity on the Arizona side of the river. Arizona Attorney General Arthur La Prade concluded that the Metropolitan Water District had no right to build on Arizona's territory, which prompted Governor Moeur to send a larger National Guard force to halt construction. The troops were recalled when Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes halted construction until the issue had been settled. The Department of the Interior took Arizona to court over the issue hoping to end the state's interference. To the Department of the Interior's shock, the Supreme Court sided with Arizona and dismissed the injunction. The court concluded that the dam had never been directly approved by Congress and that California was not entitled to build on Arizona's land without Arizona's consent. Arizona eventually agreed to allow the dam in exchange for approval of the Gila River irrigation project.^ |

|

|

| (1941)^ - Map showing the Colorado River Aqueduct from where it starts at Parker Dam to the Cochella Tunnels. |

|

|

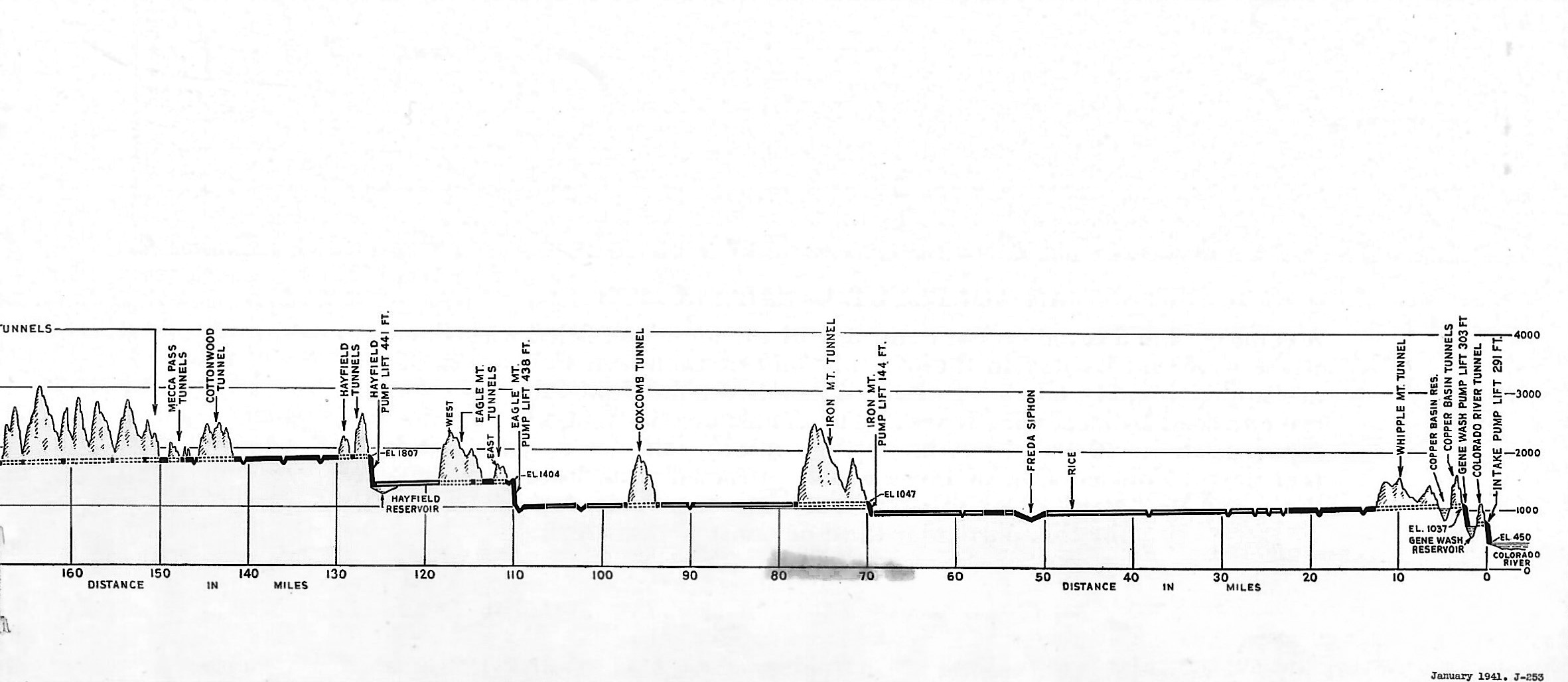

| (1941)^ - Profile view of the Colorado River Aqueduct showing the uneven terrain and elevation gain by which the water needed to be pumped over or tunneled through. |

Historical Notes There are five pumping plants on the aqueduct, and together they lift the water a total height of 1617 feet in crossing mountain barriers standing between the river and the cities of the Metropolitan Water District. |

|

|

| (ca. 1935)^*- Side view of the Intake Pumping Plant located on the California side of the Colorado River. Photo courtesy of Mary Jo Holmes in Memory of her Father, Joseph Holmes, who worked on the construction of the aqueduct.^* |

Historical Notes Here water is taken from the river and pumped 291 feet up a sheer mountainside and into the first of 39 tunnels on the aqueduct system. |

.jpg) |

|

| (ca. 1935)^*- Intake pumping plant of the Colorado River Aqueduct located on the California side of the Colorado River, two miles upstream from Parker Dam. |

Historical Notes There are five pumping plants on the aqueduct, and together they lift the water a total height of 1617 feet in crossing mountain barriers standing between the river and the cities of the Metropolitan Water District. |

|

|

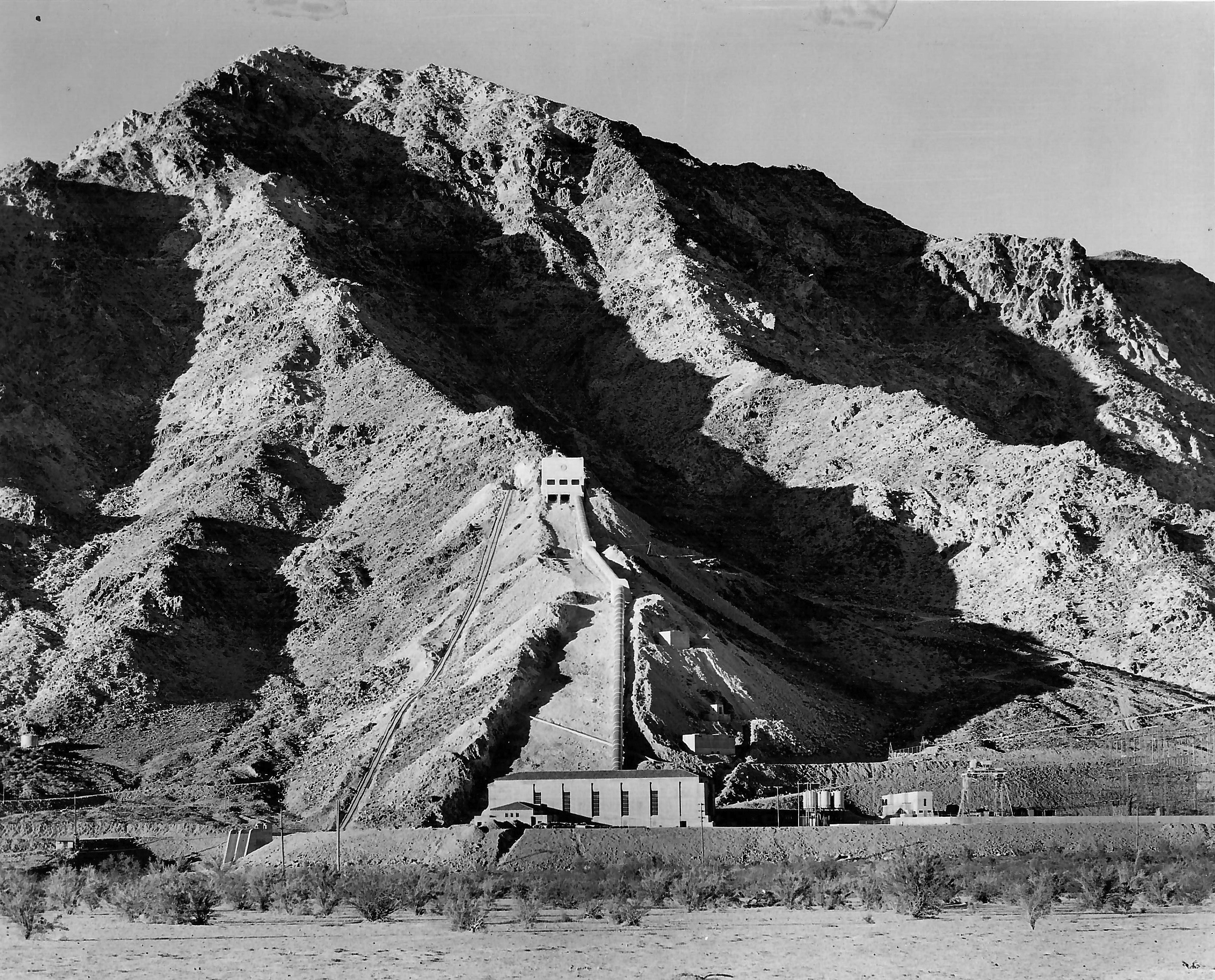

| (ca. 1938)^*- View showing the Eagle Mountain Pumping Plant. Located at the base of the rugged Eagle Mountain in the midst of the desert, it is one of the five huge pumping plants on the Colorado River Aqueduct. The pumping plant lifts aqueduct water up to the ridge of this mountain in order to gain elevation in crossing the sesert wastelands. |

|

|

| (1937)^ - Building an aqueduct siphon. A view of siphon construction as seen from the inside of a section of covered conduit on the Colorado River Aqueduct. |

Historical Notes The main line of the aqueduct includes 54.1 miles of these 16-foot diameter concret conduits which have a capacity of 1500 cubic feet of water per second, or approximately one billion gallons of water per day. The water seen on the floor of the conduit was placed there for curing purposes during the construction period. Construction of the conduits alone on the Colorado River Aqueduct involved the excavation of nearly 12 million cubic yards of earth and rock, and the placing of 1,200,00 cubic yards of concrete. |

|

|

| (1937)^ - Monolithic siphon construction on the main aqueduct. This particular siphon has an inside diameter of 12 feet 4 inches. |

Historical Notes The main line of the Colorado River Aqueduct includes 144 separate inverted siphons which vary in length from 175 feet to five miles, and have a combined length of approximately 29 miles. These inverted siphons are of three distinct types: single circular barrel, as shown above; double parallel circular barrel; and three-compartment rectangular. |

.jpg) |

|

| (ca. 1935)^*– View showing the Eagle Mountain Siphons. Here the aqueduct rides the ridge of the towering Eagle Mountains for a distance of several miles. |

|

|

| (ca. 1935)^*- Winding its way across desolate desert country is seen the concrete conduit section of the Colorado River Aqueduct after the concrete work had been completed but before the dep trench in which it was placed had been backfilled. |

|

|

| (ca. 1935)^ - View showing the Copper Basin Dam. This dam creates a beautiful reservoir of blue water in the heart of the desert. |

Historical Notes The Copper Basin Reservoir is one of two operating reservoirs located near the aqueduct’s intake on the Colorado River. The dam shown above reaches into the air 210 feet above the desert floor. More than 250 feet long at its crest, the base of the canyon that it blocks is less than 20 feet in width. |

|

|

| (ca. 1938)^*- View showing a man sitting at lower right looking down at two men looking as small as ants standing on the Copper Basin siphon. |

Historical Notes The Copper Basin siphon is one of the more spectacular links in the 392-mile-long Colorado River Aqueduct. It is an inverted siphon constructed with reinforced concrete, with an inside diameter of 16 feet, connecting two aqueduct tunnels separated by a deep canyon. There are 144 siphons of various types on the aqueduct. |

|

|

| (ca. 1935)^ - A section of precast concrete pipe being lowered into a trench where it became a part of the distribution system of the Colorado River Aqueduct. |

Historical Notes The above section has an inside diameter of 10 feet 3 inches. Other sections of this line have inside diameters as great as 12 feet 8 inches. Some of these huge sections of pipe, which were 12 feet in length, weighed as much as 42 tons. |

|

|

| (ca. 1935)^ - Welding a Steel Aqueduct Pipe. View showing a welder in action on the inside of the Palos Verdes Feeder of the Distribution System. |

Historical Notes This particular section of the feeder is constructed of welded steel pipe having an inside diameter of 51 inches. Before being place in the trench, the interior of these pipe sections was lined with cement mortar centrifugally applied, and the outside of each section was coated with gunite. The picture shows a welder making the inside field weld at a joint connecting two sections of pipe. |

|

|

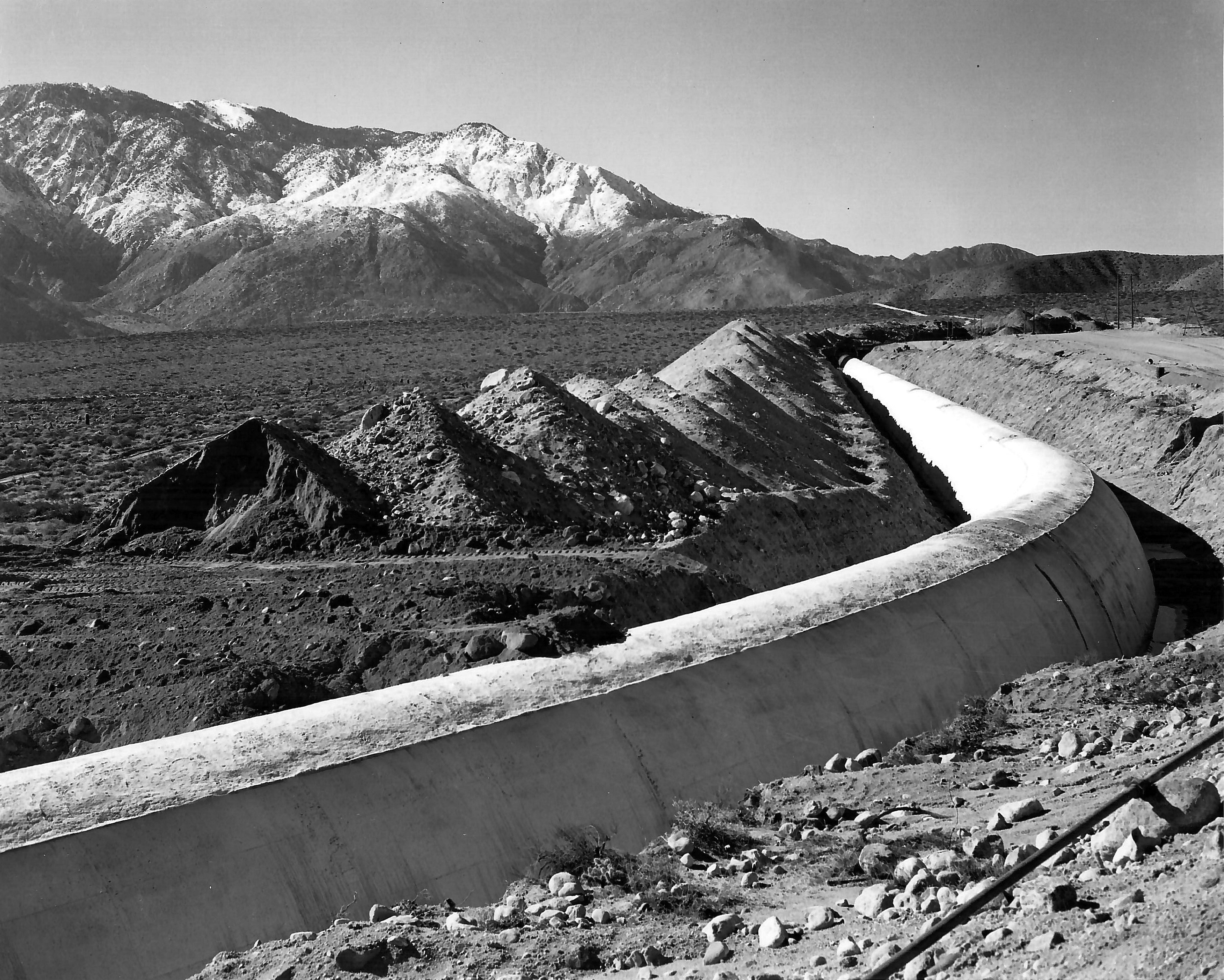

| (ca. 1935)^*- A concrete-lined canal section of the Colorado River Aqueduct. Sixty-three miles of the aquedut line, where it crosses level desert land, takes the form of concrete-lined canals. |

|

|

| (ca. 1938)^*- View showing Hayfield Pumping Plant. It is the most westerly of the five aqueduct pumping plants and located 126 miles west of the Colorado River. |

Historical Notes The Hayfield Pumping Plant lifts the aqueduct water 441 feet and delivers it into the portal of the Hayfield mountain tunnel, from which point the water flows by gravity all the way to the original 13 cities of the MWD. |

|

|

| (1938)^ - View showing the final holing through of the 13-mile San Jacinto Tunnel on Nov 19, 1938. |

Historical Notes The San Jacinto Tunnel became famous because of the tremendous amount of underground water that was encountered during its construction, and it is said to have been the most difficult tunnel that has ever been driven. It was but only one of the 42 separate tunnels on the Colorado River Aqueduct. All, but the San Jacinto Tunnel, were completed by July, 1937, well in advance of schedule. |

|

|

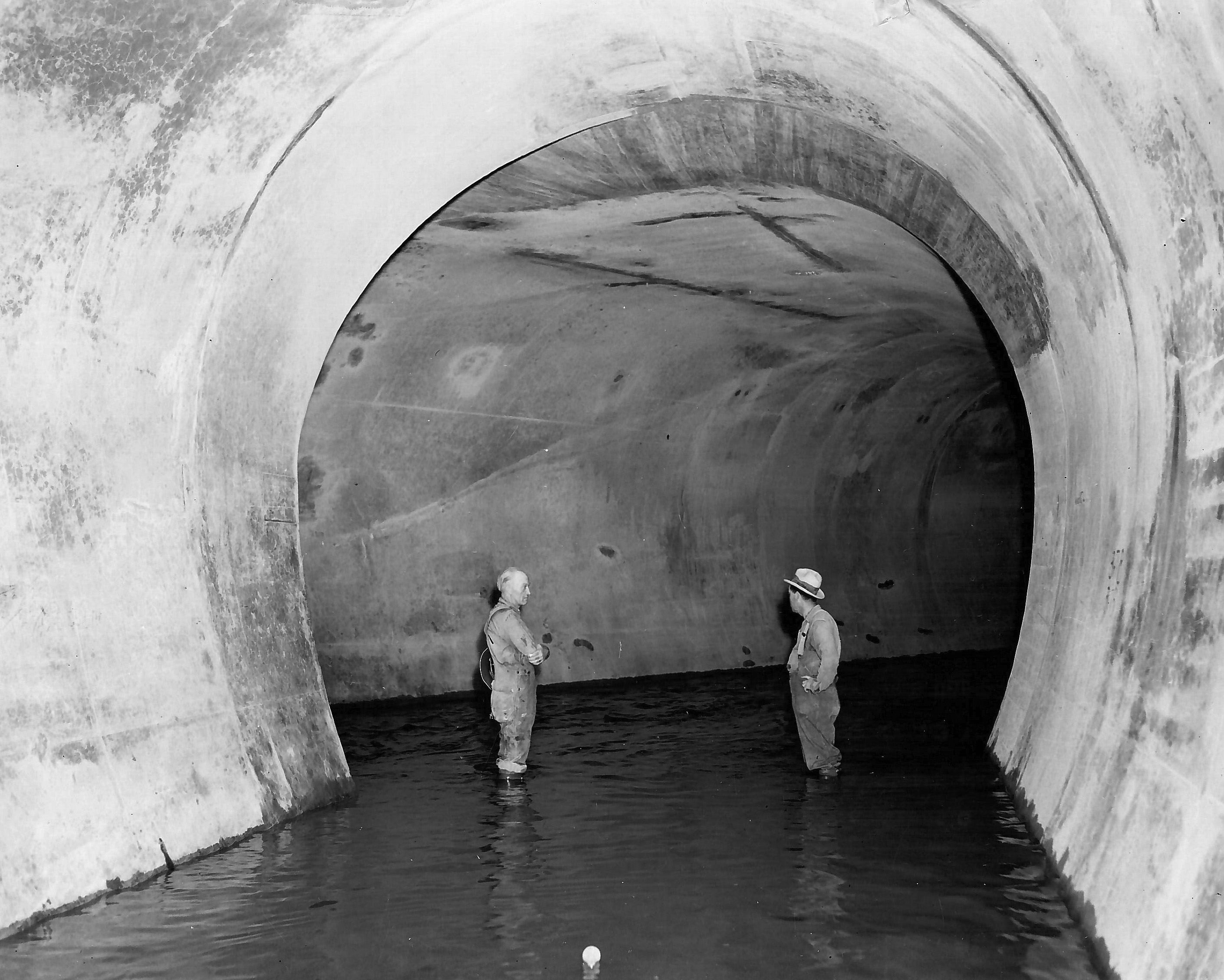

| (ca. 1938)* - Inside the 16-foot-diameter San Jacinto Tunnel as the first aqueduct water began to flow through this link of the giant man-made water way. |

Historical Notes San Jacinto Tunnel, 13 miles in length, is the second longest tunnel on the aqueduct system, the longest being the East Coachella Tunnel, 18 miles in length. |

|

|

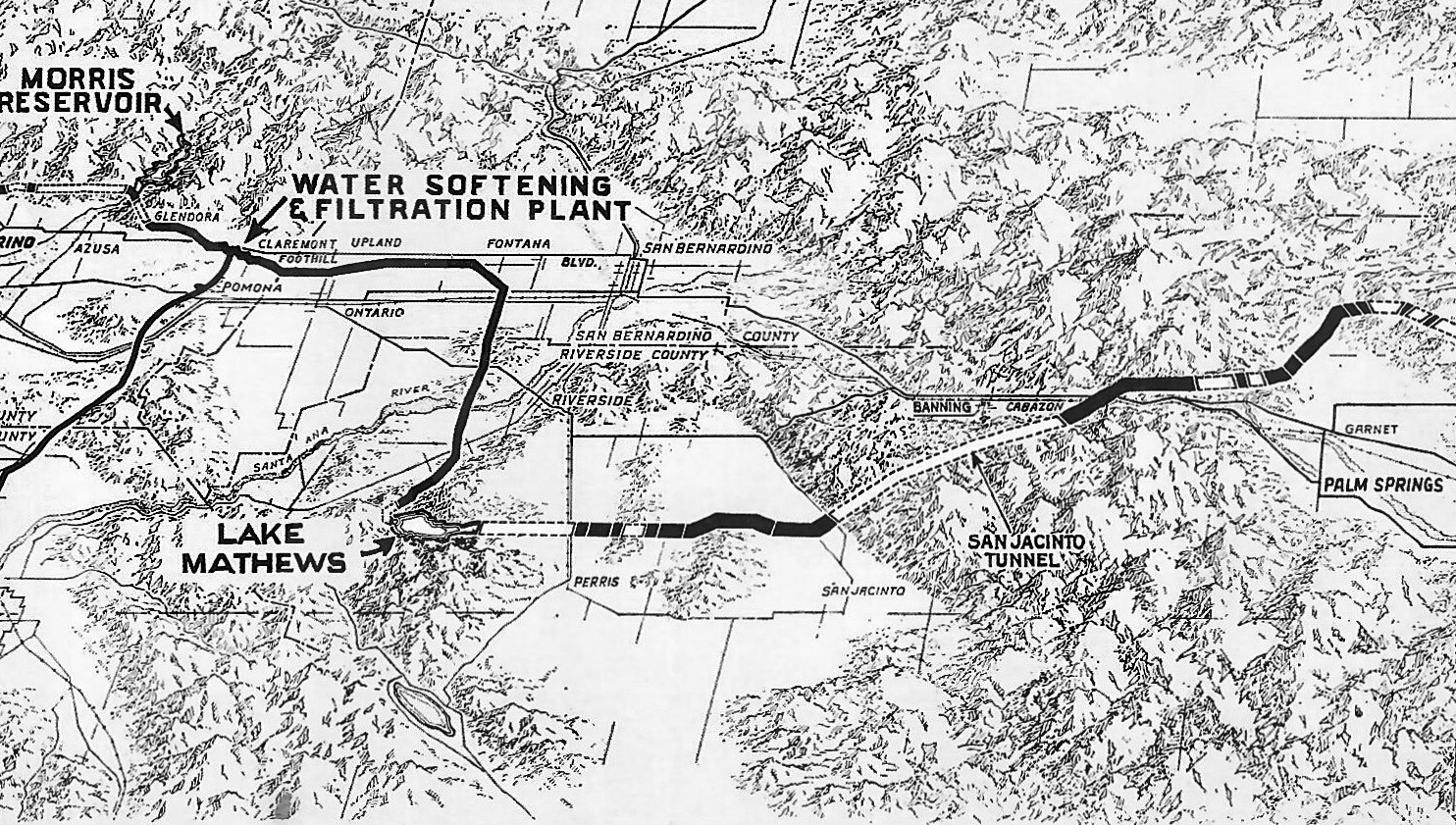

| (1940s)^ - Map showing the Colorado River Aqueduct from near Palm Springs to to the Morris Reservoir near Glendora. The 13-mile San Jacinto Tunnel is seen at center-right. |

|

|

| (1935)^ - Four power shovels were required in the borrow pits to feed the constant stream of trucks which carried material to the earth-fill construction of the Mathews dam and dike. This work went ahead twenty-four hours a day, and at times more than 100,000 cubic yards of earth per week were placed and compacted on the structures. |

Historical Notes This man-made lake was created in a huge natural basin by the construction of a dam 210 feet high and a third of a mile thick at its base, and by a 90-foot-high dike, a mile and a half long. The reservoir had a storage capacity of 107,000 acre feet, or 34,000,000,000 gallons (1935). |

|

|

| (ca. 1935)^*– Lake Mathews - terminal storage reservoir on the main line of the Colorado River Aqueduct.. |

Historical Notes Lake Matthews, the main storage unit of the Aqueduct distribution system, is situated between the terminus of the main aqueduct and the head of the distibution lines, about 60 miles easterly from Los Angeles. The purpose of this reservoir is to insure an ample supply of water near the points of use as a safeguard against interruptions of flow through the main aqueduct and to regulate the uniform flow of the aqueduct to meet the fluctuation demands on the distribution system. |

|

|

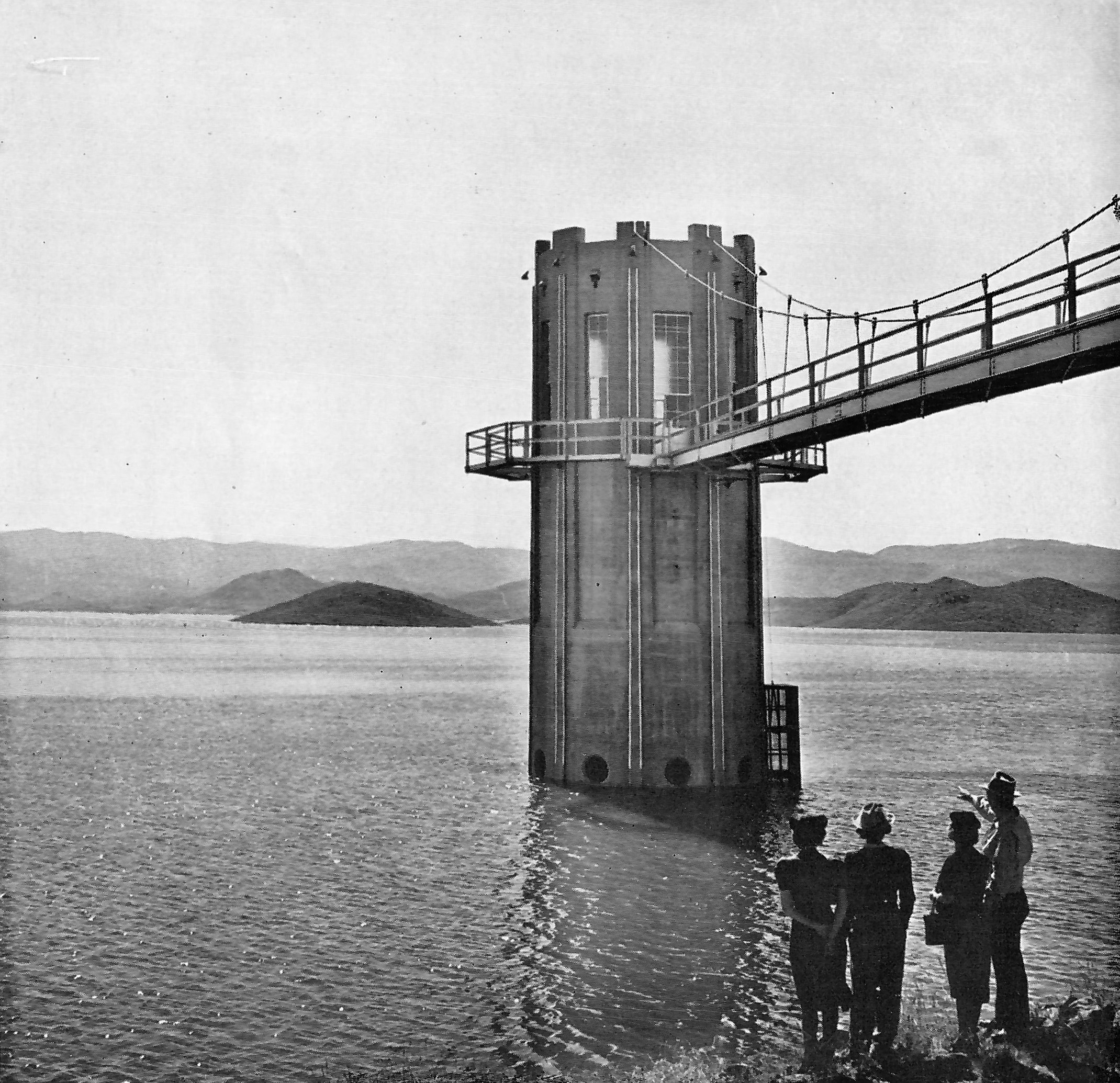

| (ca. 1935)^*- Close-up view of Lake Mathews showing a section of the reservoir dike and outlet tower. From here, 156 mi of distribution lines, along with eight more tunnels, delivers water to member cities. Some of the water is siphoned off in San Jacinto via the San Diego canal, part of the San Diego Aqueduct that delivers water to San Diego County. |

Historical Notes Through portals in the outlet tower, water is released from the reservoir to be distributed through 155 miles of conduits and tunnels to the thirteen cities (1935) of MWD which included: Los Angeles, Anaheim, Beverly Hills, Burbank, Compton, Fullerton, Glendale, Long Beach, Pasadena, San Marino, Santa Ana, Santa Monica, and Torrance. |

|

|

| (ca. 1935)^ – View showing three women and a man looking toward the outlet tower at Lake Mathews. This is the terminal reservoir of the main line of the Colorado River Aqueduct. |

Historical Notes Located at the western end of the main aqueduct, Lake Mathews also serves as the headwaters of the aqueduct’s distribution system. It had an intinital capacity of 107,000 acre feet of water and was built to have an ultimate capacity of 225,000 acre feet. |

|

|

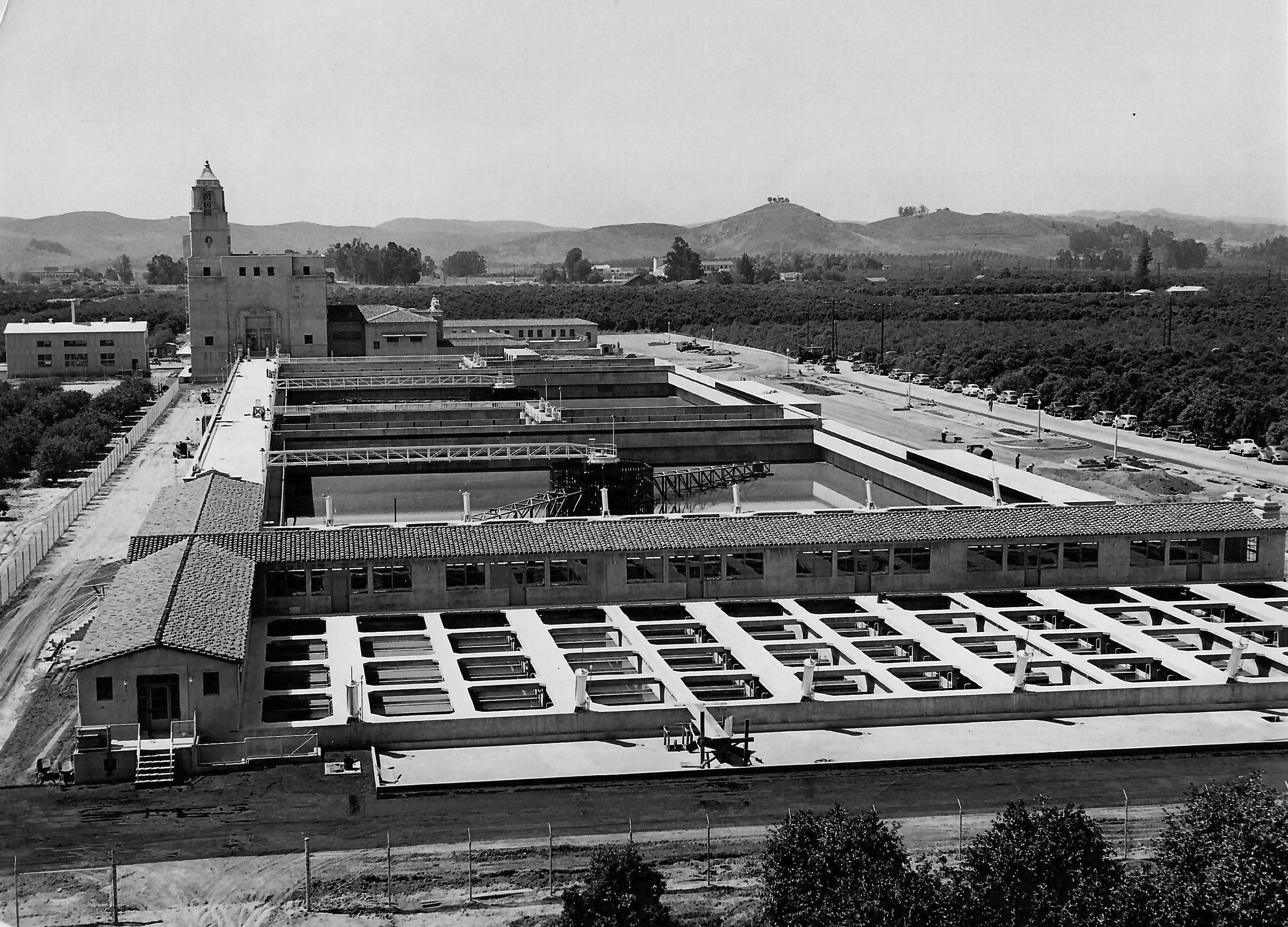

| (ca. 1938)^* - View showing the Softening and Filtration Plant located on the western end of the aqueduct system and near the original thirteen cities that made up The Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. Photo courtesy of Mary Jo Holmes in Memory of her Father, Joseph Holmes, who worked on the construction of the aqueduct.^* |

|

|

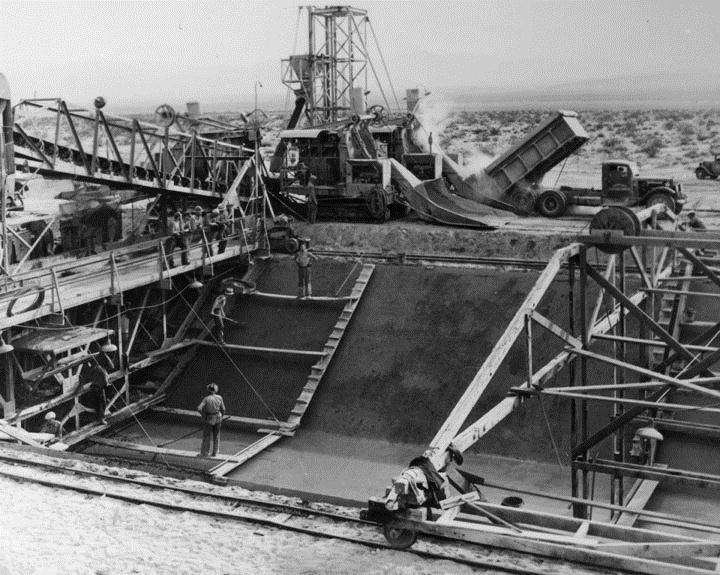

(ca. 1933)* - Empty reservoir on the Colorado Aqueduct. An aerial view of an empty Colorado River Aqueduct reservoir under construction in the 1930s. |

|

(ca. 1938)* - Colorado Aqueduct construction - The Colorado River Aqueduct, built 1935-1941 by the Metropolitan Water District (MWD). |

|

|

| (1930s)* - Colorado River Aqueduct Engineering Team |

|

|

| (June, 1941)* - Ellis Davey (MWD) and B. W. Weaver (DWP) turn 30" valve that lets the first Colorado River water into the city system - Ascot Reservoir. |

|

| (1977)* - Caption Reads: "The MWD Colorado River Aqueduct is brimful now that it is operating at 20 per cent above design capacity". Photograph dated: June 23, 1977. |

|

|

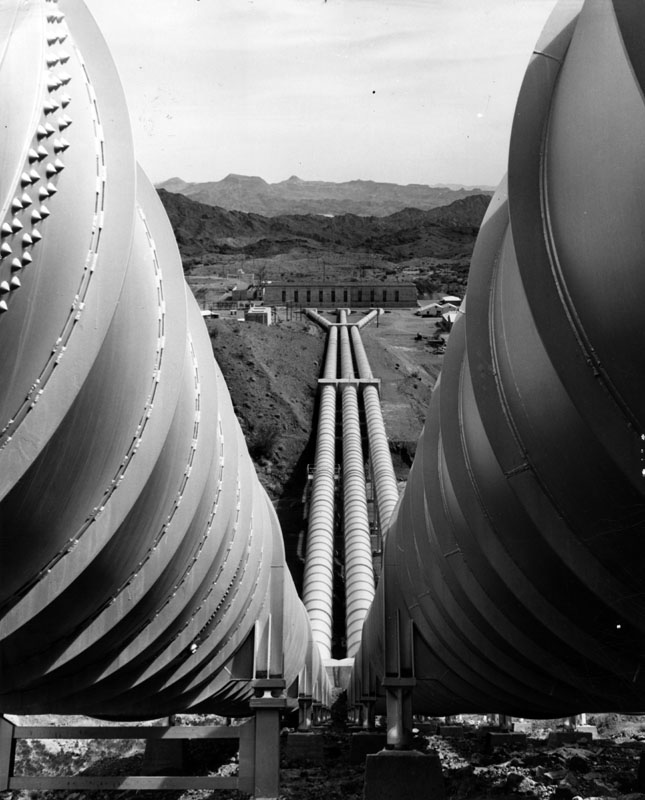

| (1977)* - Photograph caption reads: "Like huge arms, giant pipes carry Colorado River water to Southern California from the Gene Pumping Plant on the Colorado River Aqueduct. The plant, second of five on the system, is located 3 miles east of the Colorado River". The Gene Pumping Plant is just south of Parker Dam and lifts the water 303 feet. |

Historical Notes In 1955, the Colorado River Aqueduct was recognized by the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) as one of the "Seven Engineering Wonders of American Engineering". |

Construction of the Colorado Aqueduct

Click HERE for a short video. |

Click HERE to read 'Mulholland and the Colorado River Aqueduct' from LADWP's Historic Archive. |

* * * * * |

History of Water and Electricity in Los Angeles

More Historical Early Views

Newest Additions

Early LA Buildings and City Views

* * * * * |

References and Credits

* DWP - LA Public Library Image Archive

^ The Great Aqueduct - The Metropolitan District of Southern California

** LADWP: History of the Colorado River Aqueduct

*# Claremont Colleges Digital Library

^^ YouTube - Construction of the Colorado Aqueduct to Southern California

*^ Wikipedia

< Back

Menu

- Home

- Mission

- Museum

- Major Efforts

- Recent Newsletters

- Historical Op Ed Pieces

- Board Officers and Directors

- Mulholland/McCarthy Service Awards

- Positions on Owens Valley and the City of Los Angeles Issues

- Legislative Positions on

Water Issues

- Legislative Positions on

Energy Issues

- Membership

- Contact Us

- Search Index